The London Taxi Company v Frazer-Nash Research Limited, Ecotive Limited: Infringement of a 3D Trade Mark

Introduction

In “Could the Shape of Kit Kat's Chocolate-coated Wafer Be Registered as a 3D Trade Mark?”, we discussed the necessary requirements to a successful trade mark application, in particular three-dimensional trade mark applications which rely on the shape as the basis of the mark.

In the recent decision of The London Taxi Corporation Limited trading as the London Taxi Company v Frazer-Nash Research Limited, Ecotive Limited [2017] EWCA Civ 1729, the Court of Appeal upheld the ruling of the High Court, holding that the shape of the traditional “Hackney cab” trademarked by the London Taxi Company (“LTC”) was not validly registered as the shape lacked distinctive character. Further to Kit Kat’s example, it reemphasizes the difficulty for proprietors of three-dimensional (“3D”) marks seeking to obtain a permanent monopoly in protecting a certain shape that represents their brand, whether or not that shape is iconic.

Background

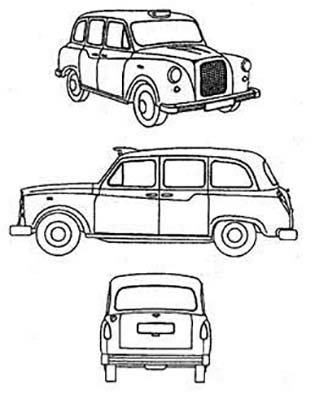

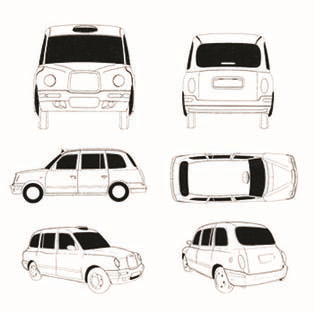

LTC was the successor in title to the manufacturer of the Fairway, TX4, TXII and TX1 models of the London taxi, which were the predominant models then used in the licensed London taxi fleet of 2015. LTC is the registered proprietor of a community trademark for its old Fairway taxi model, and a United Kingdom trademark for its TX1/ TXII taxis, all of which are three-dimensional trademarks.

|  |

Community Trade Mark based on the Fairway model | UK Trade Mark based on the TX1 and TXII models |

Frazer-Nash Research Limited (“Frazer-Nash”) and Ecotive Limited (“Ecotive”) were competitors of LTC who were then in the process of designing a new eco-friendly cab model that resembles a classic London taxi – namely the Metrocab.

It was alleged that Frazer-Nash and Ecotive intended to deceive the public as to the origin of their new Metrocab by deliberately adopting a shape which closely resembled LTC taxis, and by launching and marketing the Metrocab, they will commit trademark infringement and passing off.

The High Court dismissed both of LTC’s claims and LTC appealed. In the Court of Appeal, the main issues of debate fells on the following three heads:

1. For the purposes of assessing validity and infringement of the trademarks, who is the average consumer: (a) the taxi driver who purchases the cab or (b) the taxi driver who purchases the car together with members of the public who hire taxis (“taxi hirers”)?

2. Are LTC’s registered three-dimensional trademarks invalid because they are devoid of inherent and acquired distinctive character?

3. Are the trademarks invalid because they consist of a shape which gives substantial value to the goods?

Legal Analysis

The average consumer

In determining whether the similarities between a mark and an alleged infringing sign are sufficient as to be likely to be cause confusion, the perspective of the reasonably well-informed and observant “average consumer” should be used. The High Court concluded that the average consumer did not include taxi hirers as they were not end users of the goods, but merely users of the service provided by the consumer of the goods (i.e. taxi drivers). Moreover, taxi hirers did not take complete possession of the goods, nor did they pay a high level of attention towards who was the manufacturer of the taxi.

However, the Court of Appeal disagreed with such analysis. Noting that the purpose of a trademark is to operate as a guarantee of origin to those who purchase or use the product, an “average consumer” should include any class of consumer to whom the guarantee of origin is directed and who would be likely to rely on it. Taxi hirers may be concerned as to who is the manufacturer of the taxi in situations when there are dissatisfactions not related to the taxi service but the taxi itself. Therefore taxi hirers should not be excluded in principle as average consumers.

Distinctive character of three dimensional marks

(1) Inherent distinctive character

The High Court came to the conclusion that LTC’s registered shape lacked inherent distinctive character. Three dimensional marks are different from conventional word/ figurative mark as average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions as to the origin of products based solely on its shape, hence it is more difficult for three-dimensional marks to establish inherent distinctive character. The trademark has to depart significantly from the norm or customs of the relevant sector.

LTC attempted to argue that specific models of taxis made and sold should be taken into account, however, the Court of Appeal affirmed the High Court decision, holding the relevant sector should be viewed from a wider perspective to include not just models in production at the date of application, but also those modern designs on the road which the average consumer can be expected to have seen. In the current case an average consumer of taxis would merely perceive LTC’s registered trade marks and the Metrocab as variations of the typical shape of taxis.

(2) Acquired distinctive character

The test in Société des Produits Nestlé SA for approaching the issue of acquired distinctive character was adopted by both courts: whether trade mark identifies the relevant goods as originating from a particular undertaking and can be distinguished from goods of other undertakings. Factors such as market share held by the goods bearing the mark, how geographically widespread and long-standing the use of the mark has been, proportion of the relevant class of persons who perceive the goods or services as emanating from the proprietor etc should be considered. It was recognized that none of the abovementioned factors, whether individually or in combination, would justify an inference that taxi hirers could identify LTC taxi’s by merely their shape, particularly when the identity of the manufacturer was a matter of indifference to the consumers.

LTC further submitted they had expended significant sums in advertising, promoting the shape of the taxi as an indication of origin and educating the public. The Court of Appeal was not persuaded by the evidence to depart from the High Court’s decision and held the advertisements were not adequate to establish taxi hirers, or even merely taxi drivers, were interested and so educated in whether the shape of the taxi is an indicated of a unique trade source.

(3) Substantial value

A 3D trademark would be invalidated if it consists exclusively of the shape which gives substantial value to the goods. It was held by the High Court that the average consumer in UK placed value on the shape of a typical London taxi, but not the shape of taxis manufactured by LTC (e.g. the Fairway, TXII).

The Court of Appeal further explained in assessing whether the mark adds substantial value to the goods, goodwill generated by the trademark should be disregarded; the focus is whether the shape itself adds substantial value. Yet, the court considers that the current guidance is not clear cut, and there may be other factors such as the presence or availability of design protection that may affect the analysis.

Implications

The lost battle by LTC in the appeal case has implications that go beyond finding LTC’s shape marks to be invalid, or permitting Frazer-Nash and Ecotive in their production of the new eco-friendly Metrocab. The Court of Appeal also left open several questions: whether the notional “average consumer” should definitively include taxi hirers as end users, and when addressing substantial value of a trademark, whether the fact that consumer will recognize a specific shape as that of a typical item of that sector should be taken into account.

However, one thing is for sure: in order for proprietors to protect and enforce trademark rights in three-dimension shapes, the trade mark must clearly act as a badge of origin and possess distinctive character differentiating it from the norms of the relevant sector. The closer the shape for which registration is sought resembles the natural shape used for the particular products, the less likely it will be considered distinctive enough to be registrable. Trade mark offices and the Courts’ continuous reluctance in permitting 3D logo/trade mark registration may serve as caution to those who attempt to ultimately stifle legitimate competition by way of registering 3D shapes.

For enquiries, please contact our Intellectual Property & Technology Department: |

E: ip@onc.hk T: (852) 2810 1212 19th Floor, Three Exchange Square, 8 Connaught Place, Central, Hong Kong |

Important: The law and procedure on this subject are very specialised and complicated. This article is just a very general outline for reference and cannot be relied upon as legal advice in any individual case. If any advice or assistance is needed, please contact our solicitors. |

Published by ONC Lawyers © 2017 |