Privy Council Holds Backward Tracing Available in Fraud Cases

Introduction

On 3 August 2015,

the Privy Council handed down its judgment in Federal Republic of Brazil and another v Durant International Corpn

and another [2015] UKPC 35, in which Lord Toulson, delivering the

judgment on behalf of the Board, affirmed the doctrine known as “backward tracing”.

The doctrine describes where the claimant’s property is traced into an asset

the defendant already has and no direct connection can be established between

the misappropriated trust funds and the assets acquired by the perpetrators.

Background

The Municipality

of Sao Paulo (“Municipality”), being

the effective claimant, brought proceedings in Jersey against the Defendants (“Durant” and “Kildare”), which were BVI companies controlled by the former mayor

of the Municipality, Paulo Maluf (“PM”),

and his son Flavio Maluf (“FM”). It

was alleged that bribes totalling US$10.5 million, in connection with a major

road building contract in Sao Paulo, had been paid to PM and then laundered

through bank accounts belonging to FM and the two companies. The Municipality

sought to trace into funds held by Durant and Kildare in order to recover the

proceeds of these secret payments.

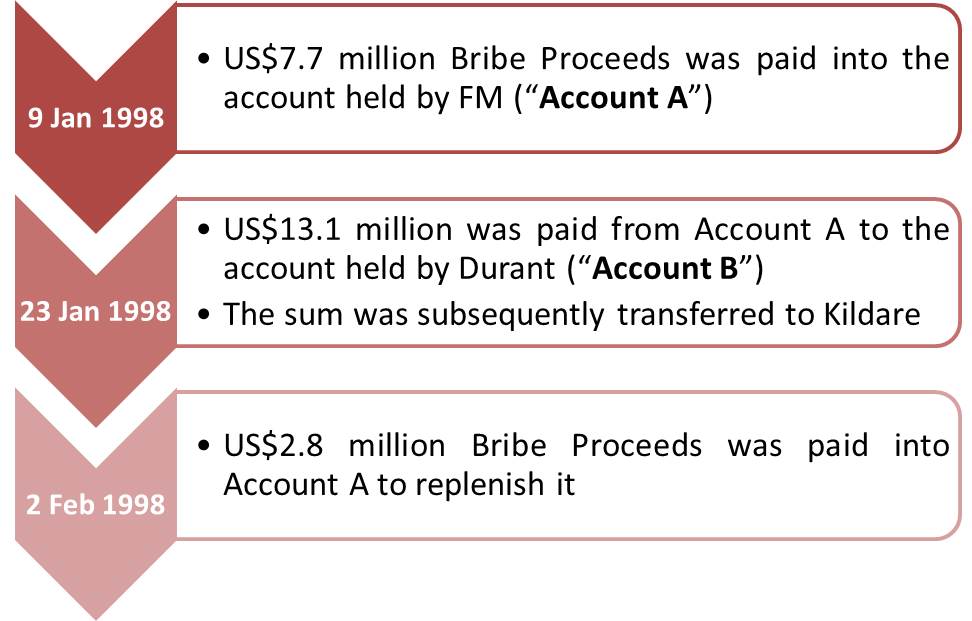

Chronology of the

events can be summarized as follows:-

The Royal Court of

Jersey found the Defendants liable to the Municipality as constructive trustees

of US$10.5 million. This was upheld on appeal. When the case reached the Privy

Council, the BVI companies no longer challenged the Jersey court’s finding that

they were liable to the Municipality as constructive trustees. The dispute was

over the extent of that liability. The Defendants argued that they were only

liable for the lesser sum of US$7.7 million because the remaining US$2.8

million was paid into Account A to replenish it, after payment was made from

Account A to Account B. One of the arguments raised by the Defendants was that

the remaining US$2.8 million cannot be traced as there is no sound doctrinal

basis for “backward tracing”.

Conventional

tracing claims

The conventional

doctrine of tracing involves rules which govern whether one form of property

interest can properly be said to be regarded as substituted for another. It

starts with the claimant’s original property interest and studies what has

become of it. Thus, the equitable remedies of tracing required the “continued

existence of the money”: In re Diplock

[1948] Ch 465 at 521. And there could be no tracing remedy against an asset

acquired before misappropriation of money took place, since a property interest

cannot turn into, or provide a substitute for something which the holder

already has: Bishopsgate Investment

Management Ltd v Homan [1995] Ch 211. This explains the “no backward

tracing” principle.

Privy Council decision

The Privy Council

recognized that the authorities on backward tracing were inconclusive and it is

ultimately a matter of judicial policy whether the law ought to allow backward

tracing. Importantly, the Privy Council drew attention to the “increasingly

sophisticated and elaborate methods of money laundering, often involving a web

of credits and debits between intermediaries” and emphasized that the court

“should not allow a camouflage of interconnected transactions to obscure its

vision of their true overall purpose and effect.” Lord Toulson agreed with Sir

Richard Scott V-C’s finding in Foskett

v McKeown [1998] Ch 205 that the availability of equitable remedies

ought to depend upon the substance of the transaction in question. If the court

is satisfied that the various steps are part of a coordinated scheme, the

strict order in which associated events occur should not matter. Under such

circumstances, the court should look at the transaction overall rather than

divide minutely the connected steps.

The Board therefore

rejected the argument that there can never be backward tracing. But the

claimant has to establish a co-ordination between the depletion of the trust

fund and the acquisition of the asset which is the subject of the tracing

claim, such as to warrant the court attributing the value of the interest

acquired to the misuse of the trust fund. On the question of whether or not

there was the necessary link, the Privy Council agreed with the Jersey courts’

finding that it was the defendants’ own pleaded case that the relevant payments

into Account B were linked with the payments into Account A.

Implications

The decision is of

particular importance to the victims of fraud or breach of trust claim, since

the availability of proprietary remedies is often determinative as to whether a

claimant is able to make a recovery or not. However, the Privy Council clearly

had the unsecured creditors in mind, warning that the court should be very

cautious before expanding equitable proprietary remedies in a way which may

have an adverse effect on other innocent parties. Particularly, the court expressly rejected

the suggestion that money used to pay a debt can in principle be traced into

whatever was acquired in return for the debt.

For enquiries, please contact our Litigation

& Dispute Resolution Department: |

|

E:

insolvency@onc.hk T:

(852) 2810 1212 19th Floor, Three

Exchange Square, 8 Connaught Place, Central, Hong Kong |

|

Important: The law and

procedure on this subject are very specialised and complicated. This article is just a very general outline for

reference and cannot be relied upon as legal advice in any individual case.

If any advice or assistance is needed, please contact our solicitors. |

|

Published by ONC Lawyers © 2016 |