Legal issues in Transfer of Business

Transfer of Business (Protection of

Creditors) Ord., Cap. 49

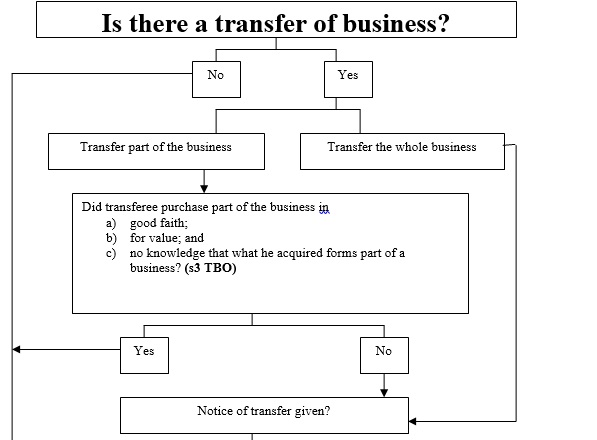

1.

Whenever

a business is transferred[1]

(with or without goodwill), the transferee shall become liable for all the

debts and obligations arising out of the carrying on of the business by the transferor:

S.3 TBO. Such liabilities are

imposed irrespective of any contrary agreement between the transferor and the

transferee.

2.

Where

only a part of a business is transferred and the transferee purchased such part

of the business in good faith and for value and had no knowledge that what he

acquired formed part of a business, he shall not be so liable.

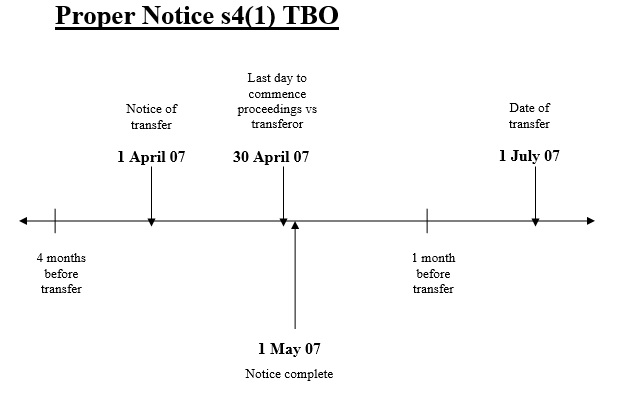

3. A transferee shall not become liable for such liabilities if a notice of transfer has been given (not more than 4 months and not less than 1 month before the date of transfer) and has become complete at the date of transfer: S.4(1) TBO.

3.1 A

notice of transfer must be given in the prescribed form.

3.2 A notice

becomes complete upon the expiration of 1 month after the date of the last

publication of the notice. The notice

must be published in the Gazette, 2 Chinese language and 1 English language

newspapers. It is the date of the last

notice that counts.

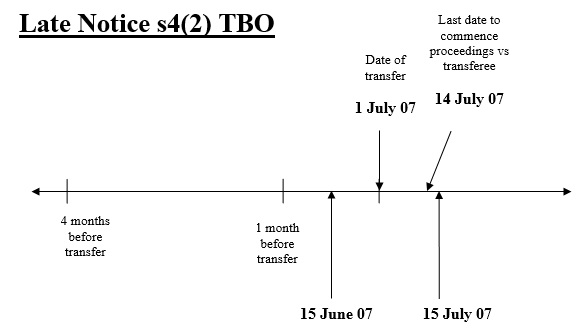

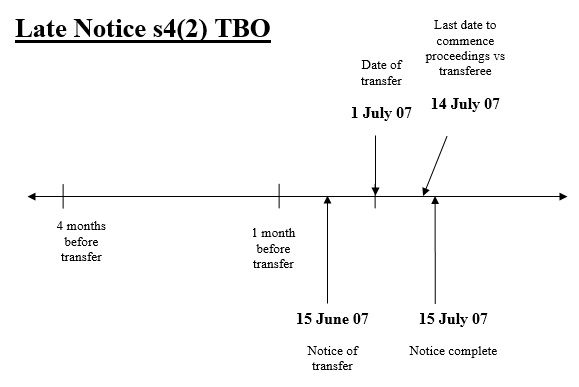

3.3 Late

Notice - Where a notice is given late (i.e. less than 1 month before the date

of transfer), the liability of the transferee ceases when the notice becomes

complete: S. 4(2) TBO.

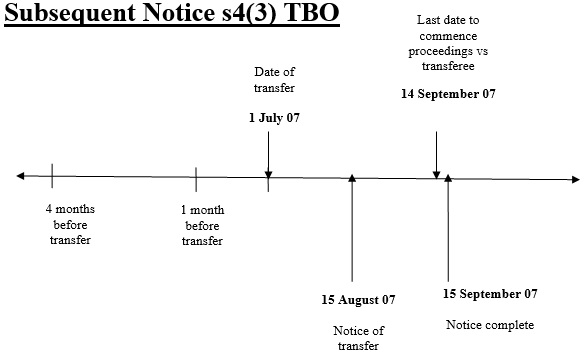

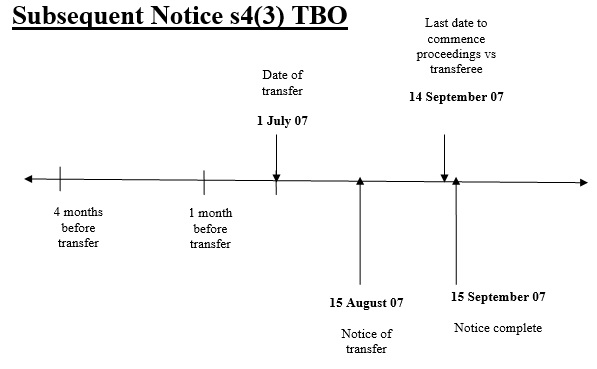

3.4 Subsequent

Notice - Where no prior notice is given before the date of transfer, the

liability of the transferee shall not cease until such a notice has been given

and become complete: S.4(3) TBO.

4.

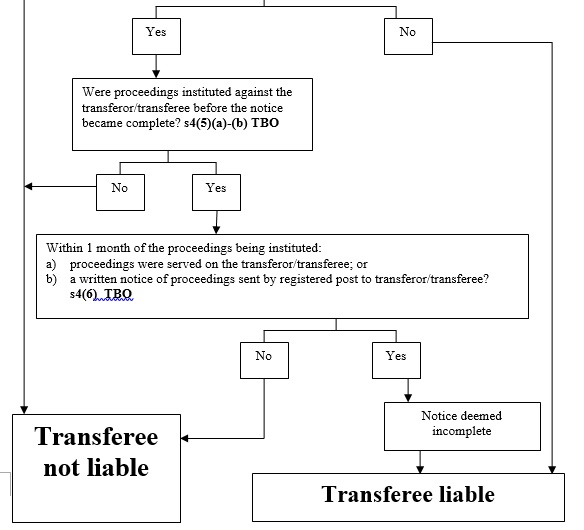

A

notice is deemed incomplete i.e. the transferee remains liable, if:

4.1 where

the notice of transfer has become compete at the date of transfer, proceedings are instituted against the

transferor before the notice has become complete; or

4.2 where

the notice of transfer has not become complete at, or where no notice was given

at all before, the date of transfer, proceedings are instituted against the

transferee before the notice has become complete.

5.

Proceedings

must be served upon the transferor or the transferee, as the case may be,

within 1 month of commencement.

Alternatively, a written notice of the proceedings must be sent by

registered post to the last known address of such transferor or transferee.

6.

A

transferee’s liability under TBO is limited to the value of the business

acquired by him (value as at the date of transfer) provided he has paid to the

creditors in discharging his liabilities under TBO in good faith and without

preference an amount equal to the value[1]: S.8

TBO. The value is presumed to be the

amount paid or agreed to be paid for the acquisition, unless the contrary is

proved.

7.

A

creditor is not entitled to institute any action against a transferee for

liabilities under TBO more than 1 year after the date of transfer: S. 9 TBO. This is an absolute bar, irrespective of

whether any notice of transfer has been given[2].

8.

The

transferee is entitled to be indemnified by the transferor (or charge-holder if

sale under charge) for all the amounts for which the transferee is made liable

under TBO: S6 TBO.

9.

The

pre-existing liabilities of the transferor are not affected or relieved under

the TBO: S. 7 TBO.

10.

TBO

does not apply to any transferee where the transfer is effected by the Official

Receiver, a trustee in bankruptcy, a liquidator of a company in liquidation

(excluding one appointed under voluntary winding-up) or, a charge-holder whose

charge has been registered for not less than 1 year before the date of transfer

etc.: S.10 TBO.

**********************************************************************

CASE STUDIES

REFCO, INC v TROIKA BULLION LTD & OTHERS, [1989] HKLY 869

P was a creditor of X and in an action to recover debts claimed

that X had transferred its business to "Y, formerly known as D".

After the limitation period under s.9 of the Transfer of Businesses (Protection of

Creditors) Ordinance had expired, P asked for leave to amend the writ and the statement of claim so as to change the

description of the first defendant from "Y formerly known as D" to

simply "D", alleging that the business had been transferred to

D and/or to Z.

The defendants sought to strike out the first defendant D and the

fourth defendant Z. P then proposed to rename the first defendant as "Z

formerly known as X" and to strike out Z as the other defendant,

thereby substituting Z as the first defendant.

Held, dismissing the action, that

(1) P's mistake was a mistake as to the identity of the defendant it

was suing, not merely a mistake as to the name of that defendant;

(2) O.20 r.5(3) permitted an amendment only to correct a genuine mistake as to the name of a defendant. It allowed this to be done even after the expiry of a relevant period of limitation. But at the same time it required the court to be satisfied that the mistake was not misleading and not such as to create any reasonable doubt as to the identity of the person intended to be sued. P's mistake was misleading, and did cause such a reasonable doubt;

(3) O.15 r.6 would not avail P as it would be wrong to substitute one

defendant for another when the claim against the original defendant was

statute-barred, unless the case was one which fell within O.20 r.5(3) (Evans

Construction Co Ltd v Charrington & Co Ltd [1983] 1 QB 810 (CA) referred to).

BNP PARIBAS v GC LUCKMATE TRADING LTD [2003] 1 HKLRD 307

(Court of Appeal)

At first instance, it was held that within the meaning of TBO, B

had transferred its business to D, such that D was liable for B's liabilities;

and that D was not entitled to invoke s.8 which entitled a transferee to cap

its liability to the value of the transferor's business at the date of the

transfer. D was ordered to pay P, a creditor of B, US $999,162.62. D appealed

on the availability of s.8. D had paid US$1 for B and argued as the liabilities

of B far exceeded its assets, US$1 should be presumed to be the correct value

and its liability should be limited to this amount.

Held, dismissing the appeal, that:

(1) As it was D seeking to derive a benefit from s.8, the burden

of proof lay on D to establish that the provision was applicable. Section 8 was

not available to D because it could not prove that it had given true value

consideration for B. The purely notional sum paid in consideration with nothing

having been paid to the creditors, meant that D was able to take advantage of

the assets and goodwill of the business while at the same time shedding the

responsibility for the liabilities of B. The scheme was undoubtedly designed to

defeat the claims of B's creditors.

(2)

A

transferee can only obtain the benefit of s.8 if it can prove that it has made

or agreed to make a payment to the transferor and it has paid the creditors.

The burden of establishing this must lie upon the transferee who is seeking to

assert it

Lifting the Corporate Veil

1. Sham

or facade means what is apparent is not real. Ordinary meaning of ‘sham or

facade’ was explained by Diplock LJ in Snook

v London and West Riding Investments Ltd [1967] 2 QB 786, 802 as meaning:

“acts done or documents executed by the parties to the

‘sham’ which are intended by them to give to third parties legal rights and

obligations different from the actual legal rights and obligations (if any)

which the parties intend to create”.

2. Whenever corporate form

is alleged to be a ‘facade’, a ‘device’ or ‘sham’ or ‘cloak’ to perpetrate a

wrong, the motive of the alleged perpetrator is a relevant factor. See: Ord

v Belhaven Pubs Ltd [1998] 2 BCLC 447, per Hobhouse LJ at 457

LIU HON YING v HUA XIN STATE ENTERPRISE (HONG KONG) LTD

[2003] 3 HKLRD 347

C ran a business. A debt

was owed by C to P. At the time when P

started claiming against C, D was already incorporated and commenced business.

The ultimate controlling shareholder behind C and D gradually and continuously

channelled C's business to D and eventually to E. C did not defend P's claim

against it as the common controller had already given C up.

C, D and E all ran the same delivery business and, inter alia, had

the same customers, the same offices, same staff and the same system of work,

the same key equipment, and the same telephone and fax numbers, etc.

P, in its claims against D and E, contended: (1) that within the

meaning of the Transfer of Businesses (Protection of Creditors) Ordinance,

there had been a transfer of business and assets from C to D and subsequently

also from D to E; and (2) D commenced business partly to evade the existing

liability of C, the corporate veil of C and D ought, therefore, to have been

lifted.

Held: This was a classical case where D's corporate veil should be

lifted. D was not incorporated to avoid liability but to conceal true facts and

thereby evade liability.

Using a corporate structure to avoid the incurring of any legal

obligations in the first place was not objectionable. The court's power to lift

the corporate veil did not exist for the purpose of reversing such avoidance so

as to create legal obligations.

However, using a corporate structure to evade legal obligations

was objectionable. The court's power to lift the corporate veil might be

exercised to overcome such evasion so as to preserve legal obligations (China

Ocean Shipping Co v Mitrans Shipping Co Ltd [1995] 3 HKC 123, Customs

and Excise Commissioners v Hare [1996] 2 All ER 391, Trustor

AB v Smallbone (No 3) [2001] 1 WLR 1177

applied).

SMELOAN HONG KONG LTD V WONG WING CHEUNG TRADING AS HUNG

WAN TRADING COMPANY [2006]

HKCU 1881

P is a

finance company which made certain credit facilities to H, a textiles trading

company. H’s business did not flourish so P terminated the credit facilities

and sued H for outstanding sum. P obtained default judgment. Judgment debt

remained unpaid. Hence, P sued D instead, on the basis that D is the transferee

of H’s business. D denied there was a transfer of business and contended that

he was operating a new business.

Issues:

1) Was

there a business to transfer? D’s argument was that since the business of H had

ceased to exist at the time D took over, there was no business to transfer.

2) Was

there a transfer of business?

Held:

As to

Issue 1 –

Court held that it is not necessary for the business

alleged to be transferred to be substantial or of any particular level of value

so long as there is at least something left in the way of assets or goodwill.

Court found that although the business might have been

on the verge of bankruptcy, the business had not ceased to exist and there was

a residual business (and goodwill) of H to be transferred to D.

Evidence:

(a) No formal cessation of business of H

before D commenced business.

(b) No evidence of any notices having

been given to the customers of H.

(c) Former customers of H continued to

purchase textiles from D.

(d) D took over stock, furniture and

machine previously belonged to H.

(e) D’s business employed the same staff

as H for one month after D had taken over the business.

As to

Issue 2 –

Court

found that there was a transfer of business.

Evidence:

(a) An agreement was reached between the

shareholders of H to transfer the business of H in order to set off the sum D

had lent to H.

(b) One of H’s shareholders was in fact

D’s wife.

(c) The same shop premises was used by D.

(d) D took over stock, furniture and machine

previously belonged to H.

(e) Although the names of the 2

businesses were different, D continued to carry on the same business and served

at least some of the old customers.

[1] As per Deputy Judge Reyes in BNP

Paribas v Luckmate [2002] HKLRD 156:

“From

the above survey of case law, I derive the following principles:

(1) In deciding whether there has been a transfer of business

under the TBO, the court objectively considers all surrounding circumstances.

The fact that there is no document formally evidencing a transfer is not

conclusive.

(2) A transfer of assets may indicate a transfer of business. But

a transfer of assets does not of itself mean that there has been a transfer of

business within the TBO.

(3) There may be a transfer where the alleged transferee can be

shown to have gained some advantage from taking over the purported transferor's

business. Such advantage will often arise because the alleged transferee is

shown to have taken over a 'going concern'. But even where an entity is on the

verge of bankruptcy, an alleged transferee may perceive a real benefit to be

gained from assuming some or all aspects of that entity's business.

(4) Factors indicating that a business has been transferred from

one person to another include the following:

(a) Use of the same or similar name.

(b) Assignment of goodwill.

(c) Use of the same premises.

(d) Use of the same fixtures, fittings and equipment.

(e) Use of the same personnel.

(f) Use of the same stock-in-trade.

(g) Conduct of the same or similar type of business.

(h) Conduct of business in the same or similar manner.

(i) Servicing of the same customers.

Although the above may not be conclusive individually, the

cumulative presence of a number of the foregoing factors can establish a

transfer.”

[2] The transferee only enjoys this limitation of liability, if he has discharged liabilities arising under the Ordinance 'in good faith and without preference '. If the transferee is ignorant of some creditors who have a claim, he may well inadvertently prefer other creditors who have similar claims. The transferee's intention seems irrelevant (cf Richards & Co Ltd v Lloyd (1933) 49 CLR 49) and it is arguable that the limitation on liability will not apply at all unless the transferee pays all creditors rateably up to the limit. If this is so, the protection offered by the subsection is extremely limited (see PG Willoughby & WJL Knight, ‘Transfer of Businesses (Protection of Creditors) Ordinance’ (1980) 10 HKLJ 348, p.354): The annotated Ordinances of Hong Kong [8.02]

[3] As per Yam J in Liu Hon Ying v

Hua Xin State Enterprise [2003] 3

HKLRD 347:

“Alternatively,

on the proper construction of the Ordinance, the plaintiff submitted that s.9

only operates to bar an action against the transferee personally, and it does

not in any way seek to extinguish the liability of the transferee or to cause

such liability to cease. I accept the plaintiff's submission. Under the same

Ordinance when the Legislature intends that the statutory liability shall

cease, meaning that the transferee shall be free from such liability, it will

expressly provide that such liability 'shall cease' as in s.4(3) by giving of

the notice of transfer.

Section 9 is distinguishable from the express provision of

extinguishment of a registered owner's title to landed property under s.17 of

the Limitation Ordinance (Cap.347), which is over and above s.7 of that

Ordinance which provides for limitation to commence action. The scheme

therefore would positively extinguish title to land of a registered owner by

the lapse of time.

In the

premises under the scheme of the present Ordinance, the statutory liability of

transferee continues in law but only that by s.9 no action by creditors could

be instituted against the transferee in the courts of law. Thus, the effect of

the Ordinance would be effective when there were successive transfers with no

statutory notice being given because of deliberate concealment or otherwise.

The creditors may find themselves unable to sue the first transferee due to the

lapse of time which may be for no fault on their part. However, they should be

able to catch the last transferee if the actions against the previous

transferees could not be pursued by reason of the time-bar provided under s.9.

| For enquiries, please contact our Litigation & Dispute Resolution Department: |

E: ldr@onc.hk T: (852) 2810 1212 W: www.onc.hk F: (852) 2804 6311 19th Floor, Three Exchange Square, 8 Connaught Place, Central, Hong Kong |

| Important: The law and procedure on this subject are very specialised and complicated. This article is just a very general outline for reference and cannot be relied upon as legal advice in any individual case. If any advice or assistance is needed, please contact our solicitors. |

| Published by ONC Lawyers © 2007 |