Proving Goodwill of Get-up Without Brand Name – Not Impossible But Very Difficult

Introduction

Passing off is a cause of action to claim against a trader who take advantage of the existing reputation of another’s business (the claimant) by misrepresenting his goods and services as related to that of the claimant’s business. Such misrepresentation made by a trader is typically by way of imitating, inter alia, the trade mark, trade name of another trader and/or the packaging, label or get-up of goods of the claimant. To establish a case of passing off, the claimant needs to prove the following elements:

1. goodwill or reputation attached to the claimant’s goods or services;

2. misrepresentation by the defendant leading or likely to lead the public to believe that goods or services offered by the defendant are those of the claimant; and

3. damage suffered by the claimant.

Whilst the law of passing off is constantly evolving to combat new forms of misrepresentation, a recent judgment handed down by the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (“IPEC”) in the United Kingdom shows the limited protection to the “get-up” of products under the law of passing off. Get-up of a product generally refers to the configuration of individual elements in which products are show. These elements typically include the shape, graphics, colour combination, overall packaging or display of the same.

Brief facts

In George East Housewares Limited v Fackelmann GMBH & Co KG [2016] EWHC 2476 (IPEC), the goods concerned were kitchen measuring cups. The claimant is the successor in business to a long-established kitchenware manufacturer which sold conical measuring cups under the brand name “Tala” since 1934. The shape of their measuring cups sold has been broadly consistent throughout. The defendants are two connected companies which, respectively, manufacture and distribute measuring cups under and by reference to the names of Fackelmann and Dr Oetker. The claimant complained that the defendants, by selling in the United Kingdom measuring cups with similar get-up to those of the claimant’s, had committed passing off.

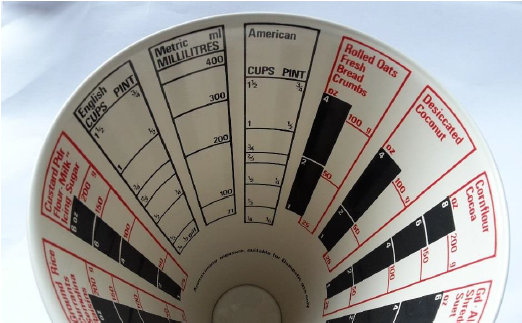

The claimant claimed that the get-up of its measuring cups has the following distinctive elements: (1) shape of the cup, (2) the “Tala” name, the design of and the wording used on each of the exterior and interior of the cups, and (3) the brand name “Tala” (collectively refers to the “Get-Up”). It gave in its pleading a detailed written description of the features of the cups to show the existence of these distinctive elements. Photos of the claimant’s and the defendants’ respective measuring cups were annexed to the judgment and reproduced as follows for illustration:

One of the measuring cups sold by the claimant (extracted from page 22 of the judgment)

Measuring cups sold by the defendants (extracted from page 24 of the judgment)

The claimant also put forward to the court as evidence a number of measuring cups it was selling or had sold in the market. Though all with a conical shape, the appearances of the exterior and interior of those cups, including their colour, have certain variations.

As the defendants’ measuring cups were sold under brand names different and distinguishable from those of the claimant’s, the claimant’s case is that there is goodwill in elements (1) and (2) of the Get-Up as stated above, either individually or in combination, such that passing off could occur regardless of the role of brand name. The major issue of the case is therefore whether the claimant could prove goodwill in the Get-Up of its measuring cups without relying on their brand names.

Case law and application by the court

A number of cases, including Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc (No.3) [1990] RPC 341 (the Jif Lemon case), the landmark case for passing off, were cited by the parties and considered by the court. Case law reveals that it is possible for a competing product to cause passing off even when no confusingly similar name is used. However, the judge in the instant case also opined that “cases in which the origin of a product is recognised regardless of the name attached to it are rare” (at paragraph 40). In other words, it is difficult (though not technically impossible) to prove that goodwill exists in features of goods such as shape and decoration without regard to the brand name of the goods.

In the instant case, the judge criticised the claimant’s written description of the features of the measuring cups as not fully supported by or consistent with all the cups put forward by it as evidence. The judge found that the detailed written description was based upon some but not all of the cups. Some cups shown to the court lacked certain features contained in the description. The discrepancies, as the judge found, are significant in terms of the overall look of the cups concerned.

In addition, there were other versions of measuring cups sold by the claimant, not put as evidence in the case, which had further differences in appearance as compared with the description. The claimant failed to give evidence to isolate out the effect of these other cups on the sale and advertising figures as at the date of the alleged passing off. Those figures could not thus show the particular goodwill in the Get-Up which is with the features described, to the exclusion of the brand name of the claimant’s products and the features of those other versions of measuring cups. The judge also found that the claimant had provided no direct evidence to support the claim that the shape of its measuring cups alone identifies the trade origin of such cups or establishes goodwill regardless of the brand name.

It was based upon these findings of facts that the judge ruled against the claimant on the issue of proving goodwill. The judge further found that, upon the evidence provided, the similarity between the claimant’s and the defendants’ measuring cups was not sufficient to cause confusion or misrepresentation for the purpose of passing off. The case was therefore ruled in favour of the defendants. No passing off was found.

Difficulties in proving goodwill as reflected from the ruling

Although the ruling of the case is fact sensitive and based largely on the evidence before the judge, the judge’s criticisms of the claimant’s evidence reflect some general difficulties for proving goodwill in get-up without regard to brand name. A business seldom sells only single homogeneous products, while any variations of appearance of the same type of products sold or modification of such products over time may damage a case of proving goodwill on get-up of the products without brand name. In terms of evidence, separate sale and advertising figures for different variations of the products, so as to show the particular goodwill of the get-up of each such variation, may be required in order to succeed in a passing-off claim based on get-up.

Given the fact that most business offers heterogeneous products in the market, the above practical difficulties of proving goodwill are significant. Litigation strategy and gathering of evidence for this kind of claim should be well planned at its beginning stage. The aforementioned difficulties should also be a factor to be taken into account for potential settlement. This case clearly demonstrates the limitation of the law of passing off and the importance of securing registered trade mark and design rights.

In view of the above, it is therefore advisable for brand owners, if and when appropriate to take steps to ensure that get-up of products is protected through other forms of intellectual property protection, such as copyright, registration of shape mark and registered designs. Registration of get-up of the product as a shape mark and/or registered designs may help to avoid the difficulties of proving goodwill of the same in future enforcement proceedings. Once so registered, a claim against any infringement of the get-up will be governed by the statutory regimes under Registered Designs Ordinance (Cap.522) and Trade Marks Ordinance (Cap.559) respectively. Claims of infringement under these statutory regimes do not require the burdensome proof of goodwill of the products, and may thus be more favourable to the claimant. It should however be noted that whether a get-up is registrable as registered designs and shape mark depends on whether on such get-up meet the criteria for registration as provided in the relevant ordinance. After all, to obtain greater protection of interest, possibility of registration of various intellectual property rights should be explored at its earliest, and in case goodwill may become an issue in future, a business should always have a good record retention practice and seek legal advice at an early stage of any potential claim.

For enquiries,

please contact our Intellectual Property & Technology Department: |

|

E: ip@onc.hk T:

(852) 2810 1212 19th Floor, Three Exchange Square, 8 Connaught

Place, Central, Hong Kong |

|

Important: The law and procedure on

this subject are very specialised and

complicated. This article is just a very general outline for reference and

cannot be relied upon as legal advice in any individual case. If any advice

or assistance is needed, please contact our solicitors. |

|

Published by ONC Lawyers © 2016 |