Could the Shape of Kit Kat's Chocolate-coated Wafer Be Registered as a 3D Trade Mark?

Introduction

The recent decision of Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd (Case C‑215/14) of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) of 16 September 2015 has clarified to some extent the requirement of distinctiveness in three-dimensional trade mark applications.

Background

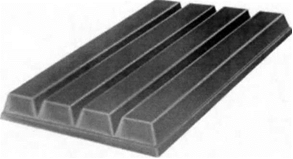

Société des Produits Nestlé SA (“Nestlé”) filed an application with the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (the “UKIPO”) to register a three-dimensional sign representing the shape of a four finger chocolate-coated wafer as a trade mark (the “Trade Mark”), in respect of certain goods in class 30 (including e.g. “chocolate”). The shape of the Trade Mark is the basic shape of Nestlé’s product “Kit Kat”, which has almost been entirely unchanged since 1935, except that the Trade Mark does not include the embossed words “Kit Kat” or sections of the oval shape which form part of the “Kit Kat” logo, as illustrated below:

|

|

(a) Actual shape | (b) Trade Mark |

After the application for the Trade Mark was published, Cadbury UK Ltd (“Cadbury”) filed an opposition against the Trade Mark application based on the Grounds of Refusal (as defined below), which was eventually largely upheld before the UKIPO (except for the goods “cakes” and “pastries”). Nestlé then appealed against the decision of the UKIPO to the English High Court, and Cadbury cross-appealed against the UKIPO’s refusal of opposition against “cakes” and “pastries”. The English High Court decided to stay the proceedings and referred 3 questions to the CJEU for an interpretation of the law (see further below).

Legal Analysis

Applicable laws

Cadbury relied on in its opposition the following absolute grounds of refusal (the “Grounds of Refusal”) under the UK national trademark law (which implements the EU Trade Marks Directive):

1. the subject trade mark is devoid of any distinctive character;

2. the sign consists exclusively of:

a. the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

b. the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result; or

c. the shape which gives substantial value to the goods,

UKIPO’s ruling

The UKIPO examiner found that the Trade Mark has 3 features:

1. the basic rectangular slab shape;

2. the presence, position and depth of the grooves running along the length of the bar; and

3. the number of grooves, which, together with the width of the bar, determine the number of “fingers”.

The examiner then took the view that the first of those features is a shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves and cannot, therefore, be registered, except in respect of “cakes” and “pastries”, for which the shape of the Trade Mark departs significantly from norms of the sector. Since the other 2 features are necessary to obtain a technical result, the examiner rejected the application for registration as to the remainder.

The examiner further dismissed Nestlé’s argument on acquired distinctiveness. Although Nestlé has shown recognition of the subject mark amongst a significant proportion of the relevant public for chocolate confectionery (only), the examiner was not satisfied that consumers have come to rely on the shape to identify the origin of the goods. Instead it seems likely that consumers rely only on the word mark KIT KAT and the other word and pictorial marks used in relation to the goods to identify the origin of the goods.

The CJEU’s answers

In determining whether the UKIPO’s decision should be upheld, the English High Court identified 3 questions of law and referred them to the CJEU for interpretation. The CJEU responded as follows:

First, the CJEU reiterated that rationale of the Grounds of Refusal 2.a. to 2.c. is to prevent trade mark protection from granting its proprietor a monopoly on technical solutions or functions characteristics of goods which a user is likely to seek in the goods of competitors. The CJEU is of the view that each of the Grounds of Refusal 2.a. to 2.c. must be applied independently of the others and if any one of them is fully applicable, a sign will be regarded as consisting exclusively of the shape of goods cannot be registered as a trade mark.

Second, the CJEU held that the manner in which the goods function is decisive from the customer’s perspective and their method of manufacture is not important. Therefore, the law must be interpreted as referring only to the manner in which the goods at issue function and it does not apply to the manner in which the goods are manufactured.

Third, the CJEU was of the view that in order to obtain registration of a trade mark which has acquired a distinctive character following use, regardless of whether that use is as part of another registered trade mark or in conjunction with such a mark, a trade mark applicant must prove that the relevant class of persons perceive the goods or services designated exclusively by the mark applied for, as opposed to any other mark which might also be present, as originating from a particular company.

Implications

According to Kerly’s Law of Trade Marks and Trade Names, The UKIPO’s decision would be affirmed unless it is wrong or unjust because of a serious procedural or other irregularity in the proceedings below. While the CJEU’s answers seem to affirm the UKIPO’s interpretation of the relevant law, unless Nestlé obtains leave to rely on new grounds and/or new evidence, or unless the UKIPO’s application of the law in, amongst others, treatment of the parties’ evidence, is flawed, the English High Court may uphold the UKIPO’s decision.

Businesses may at times be tempted to apply for registration of a more generic trade mark hoping to widen the scope of protection against potential infringers. For example, if the subject mark is successfully registered, Nestlé may enforce its rights against any undertaking which uses the registered shape in respect of the registered goods, regardless of any embossment (unless the embossment is sufficiently distinctive) or other non-distinctive features present on the undertaking’s goods. Nevertheless, this case illustrates the likelihood of absolute ground refusals against such application; some distinctive feature serving as badge of origin is required in trade mark applications (and in particular three-dimensional trade mark applications which rely on the shape as the basis of the mark).

This case serves as a reminder that a trade mark application should (i) incorporate distinctive feature(s) which could point to the applicant as the origin of the goods, and/or (ii) to the fullest extent correspond to the trade mark which has been in use in the relevant market, so as to show inherent and/or acquired distinctiveness in rebutting any absolute ground refusal.

For enquiries,

please contact our Intellectual Property & Technology Department: |

|

E: ip@onc.hk T:

(852) 2810 1212 19th Floor, Three Exchange Square, 8 Connaught

Place, Central, Hong Kong |

|

Important: The law and procedure on

this subject are very specialised and

complicated. This article is just a very general outline for reference and

cannot be relied upon as legal advice in any individual case. If any advice

or assistance is needed, please contact our solicitors. |

|

Published by ONC Lawyers © 2015 |